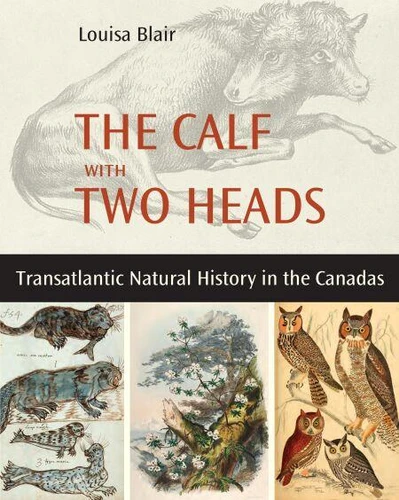

The Calf with Two Heads. Transatlantic Natural History in the Canadas

Par :Formats :

Disponible dans votre compte client Decitre ou Furet du Nord dès validation de votre commande. Le format PDF est :

- Compatible avec une lecture sur My Vivlio (smartphone, tablette, ordinateur)

- Compatible avec une lecture sur liseuses Vivlio

- Pour les liseuses autres que Vivlio, vous devez utiliser le logiciel Adobe Digital Edition. Non compatible avec la lecture sur les liseuses Kindle, Remarkable et Sony

, qui est-ce ?

, qui est-ce ?Notre partenaire de plateforme de lecture numérique où vous retrouverez l'ensemble de vos ebooks gratuitement

Pour en savoir plus sur nos ebooks, consultez notre aide en ligne ici

- Nombre de pages144

- FormatPDF

- ISBN978-1-77186-336-0

- EAN9781771863360

- Date de parution25/10/2023

- Protection num.Digital Watermarking

- Taille9 Mo

- Infos supplémentairespdf

- ÉditeurBaraka Books

Résumé

Muddy boots, cold hands, a pocket full of fossils, a mind full of existential questions.

These beautifully illustrated stories of natural history in nineteenth-century Canada are about the curious men and women who crossed the oceans from Europe to explore, map, draw, puzzle about, collect and exhibit nature in Canada. Informed by French, British and Indigenous naturalists, they tried to understand what they saw.

What did it all mean about the origins of the world?

Louisa Blair, an amateur naturalist in Quebec and a transatlantic species herself, tells tales on Darwin, Russell Wallace and James Cook, and lingers on the strange and colourful details of Canada's stubborn resistance to evolutionism and its first natural history museums with their penchant for deformities.

Louisa Blair is writer, editor and translator who was born in Quebec City, raised in the UK, and returned to live in Quebec 25 years ago.

Her books in English include The Anglos: The Hidden Face of Quebec City and Iron Bars and Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre. She has also translated numerous books and exhibitions about history, culture and politics in Quebec. Her translation of Robert Lepage's play 887 (House of Anansi Press, 2019) was nominated for a Governor General's prize. Her exhibition on natural history in Quebec, entitled Blossoms, Beetles and Birds, is on display at the Literary and History Society of Quebec. Praise and Reviews "Wow! I'm impressed.

Stop scrolling on your phones and have a look at this." Tomson Highway, Cree playwright, author, musician "These stories about the passion for nature are an antidote to climate despair." Jean-François Gauvin, Professor of Museum Studies and Scientific Heritage, Université Laval About Louisa Blair's work "A captivating book." Caroline Montpetit, Le Devoir, on The Anglos, The Hidden Face of Quebec "A loving and readable history" Brian Bethune, Macleans, on Iron Bars & Bookshelves "So good, so rich in anecdote and warm humanity, that it's hard to capture its flavour in a few lines." Morris Wolfe, Globe & Mail, on Louisa Blair's 3-part investigative piece on Indigenous land rights in the James Bay, Catholic New Times, 1992. These stories feature Indigenous mapmakers, botanical artists, bug-bitten rock fanatics, arctic explorers, and a trio of Quebec women who managed to get plants named after themselves. Blair also salutes their successors, the citizen scientists who are now frantically mapping Canada's biodiversity before it fades to bio-monotony. What does it all mean for the end of the world?

Her books in English include The Anglos: The Hidden Face of Quebec City and Iron Bars and Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre. She has also translated numerous books and exhibitions about history, culture and politics in Quebec. Her translation of Robert Lepage's play 887 (House of Anansi Press, 2019) was nominated for a Governor General's prize. Her exhibition on natural history in Quebec, entitled Blossoms, Beetles and Birds, is on display at the Literary and History Society of Quebec. Praise and Reviews "Wow! I'm impressed.

Stop scrolling on your phones and have a look at this." Tomson Highway, Cree playwright, author, musician "These stories about the passion for nature are an antidote to climate despair." Jean-François Gauvin, Professor of Museum Studies and Scientific Heritage, Université Laval About Louisa Blair's work "A captivating book." Caroline Montpetit, Le Devoir, on The Anglos, The Hidden Face of Quebec "A loving and readable history" Brian Bethune, Macleans, on Iron Bars & Bookshelves "So good, so rich in anecdote and warm humanity, that it's hard to capture its flavour in a few lines." Morris Wolfe, Globe & Mail, on Louisa Blair's 3-part investigative piece on Indigenous land rights in the James Bay, Catholic New Times, 1992. These stories feature Indigenous mapmakers, botanical artists, bug-bitten rock fanatics, arctic explorers, and a trio of Quebec women who managed to get plants named after themselves. Blair also salutes their successors, the citizen scientists who are now frantically mapping Canada's biodiversity before it fades to bio-monotony. What does it all mean for the end of the world?

Muddy boots, cold hands, a pocket full of fossils, a mind full of existential questions.

These beautifully illustrated stories of natural history in nineteenth-century Canada are about the curious men and women who crossed the oceans from Europe to explore, map, draw, puzzle about, collect and exhibit nature in Canada. Informed by French, British and Indigenous naturalists, they tried to understand what they saw.

What did it all mean about the origins of the world?

Louisa Blair, an amateur naturalist in Quebec and a transatlantic species herself, tells tales on Darwin, Russell Wallace and James Cook, and lingers on the strange and colourful details of Canada's stubborn resistance to evolutionism and its first natural history museums with their penchant for deformities.

Louisa Blair is writer, editor and translator who was born in Quebec City, raised in the UK, and returned to live in Quebec 25 years ago.

Her books in English include The Anglos: The Hidden Face of Quebec City and Iron Bars and Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre. She has also translated numerous books and exhibitions about history, culture and politics in Quebec. Her translation of Robert Lepage's play 887 (House of Anansi Press, 2019) was nominated for a Governor General's prize. Her exhibition on natural history in Quebec, entitled Blossoms, Beetles and Birds, is on display at the Literary and History Society of Quebec. Praise and Reviews "Wow! I'm impressed.

Stop scrolling on your phones and have a look at this." Tomson Highway, Cree playwright, author, musician "These stories about the passion for nature are an antidote to climate despair." Jean-François Gauvin, Professor of Museum Studies and Scientific Heritage, Université Laval About Louisa Blair's work "A captivating book." Caroline Montpetit, Le Devoir, on The Anglos, The Hidden Face of Quebec "A loving and readable history" Brian Bethune, Macleans, on Iron Bars & Bookshelves "So good, so rich in anecdote and warm humanity, that it's hard to capture its flavour in a few lines." Morris Wolfe, Globe & Mail, on Louisa Blair's 3-part investigative piece on Indigenous land rights in the James Bay, Catholic New Times, 1992. These stories feature Indigenous mapmakers, botanical artists, bug-bitten rock fanatics, arctic explorers, and a trio of Quebec women who managed to get plants named after themselves. Blair also salutes their successors, the citizen scientists who are now frantically mapping Canada's biodiversity before it fades to bio-monotony. What does it all mean for the end of the world?

Her books in English include The Anglos: The Hidden Face of Quebec City and Iron Bars and Bookshelves: A History of the Morrin Centre. She has also translated numerous books and exhibitions about history, culture and politics in Quebec. Her translation of Robert Lepage's play 887 (House of Anansi Press, 2019) was nominated for a Governor General's prize. Her exhibition on natural history in Quebec, entitled Blossoms, Beetles and Birds, is on display at the Literary and History Society of Quebec. Praise and Reviews "Wow! I'm impressed.

Stop scrolling on your phones and have a look at this." Tomson Highway, Cree playwright, author, musician "These stories about the passion for nature are an antidote to climate despair." Jean-François Gauvin, Professor of Museum Studies and Scientific Heritage, Université Laval About Louisa Blair's work "A captivating book." Caroline Montpetit, Le Devoir, on The Anglos, The Hidden Face of Quebec "A loving and readable history" Brian Bethune, Macleans, on Iron Bars & Bookshelves "So good, so rich in anecdote and warm humanity, that it's hard to capture its flavour in a few lines." Morris Wolfe, Globe & Mail, on Louisa Blair's 3-part investigative piece on Indigenous land rights in the James Bay, Catholic New Times, 1992. These stories feature Indigenous mapmakers, botanical artists, bug-bitten rock fanatics, arctic explorers, and a trio of Quebec women who managed to get plants named after themselves. Blair also salutes their successors, the citizen scientists who are now frantically mapping Canada's biodiversity before it fades to bio-monotony. What does it all mean for the end of the world?