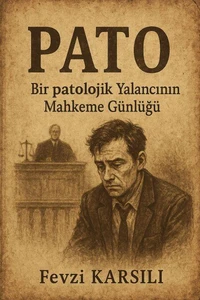

PATO is a darkly humorous and satirical novella centered on the life of a court bailiff in an imaginary Court, whose defining traits are pathological lying, narcissism, and sexual obsession. The story is not a heroic journey but a grotesque portrait of human folly, exposing how a man's desperate need for recognition turns him into an object of ridicule. The opening chapters establish Pato as an egotistical trickster figure.

He lies compulsively-not for gain but as a reflex. His deceptions are clumsy, transparent, and easily uncovered, yet he repeats them endlessly. This compulsive dishonesty becomes both his weapon and his undoing. Early scandals revolve around his inappropriate behavior toward female colleagues and his laughable attempts at seduction, which reveal his fragile masculinity and inflated self-image. A central motif is Pato's hemorrhoids, described with grotesque detail as if they were divine punishment for his arrogance.

They serve as both a literal ailment and a metaphor for his swollen vanity and chronic irritation with reality. Instead of accepting his condition, Pato dramatizes it, using his pain as yet another excuse to demand sympathy and special treatment. The novella gains psychological depth in his encounters with Abidin Bey, an older colleague who represents wisdom and moral clarity. Their dialogues resemble a philosophical interrogation of Pato's soul, with Abidin asking why he lies, what he hopes to achieve, and whether he understands what it means to live truthfully.

Pato, predictably, dodges these questions with more lies, showing his inability to face himself. The court itself becomes a theater of absurdity. Pato, in his role as bailiff, meddles with secretarial tasks, attempts to impress judges with invented knowledge, and constantly seeks validation. Instead, he earns mockery from colleagues and irritation from superiors. The court-symbol of order and law-is inverted into a stage for petty gossip, disorder, and hypocrisy.

As scandals mount, Pato's collapse accelerates. Therapy sessions and psychological reports are introduced, diagnosing him with narcissism, compulsive lying, and obsessional behaviors. Yet instead of treating these as warnings, Pato embraces them as proof of his uniqueness, convincing himself that ordinary minds cannot comprehend him. His obsessions intensify around two women: Manolya, a lawyer who embodies professional authority, and a young secretary.

His humiliating advances toward Manolya, including a scene where he kneels in her office, cement his reputation as a clown. The secretary becomes a symbol of unattainable innocence, another projection of his fantasies. In both cases, rejection only strengthens his delusions. The private chapters of the novella explore his unhappy home life. A neglected childhood and an indifferent mother left him craving validation.

His wife mocks him openly, stripping away any illusions of domestic authority. Public bravado becomes his way of compensating for private humiliation. By the final chapters, Pato has also sunk into gambling and reckless debt. In a grotesque twist, he even pursues the wife of a married debtor, blending lust, power, and financial desperation into one absurd scheme. The novella ends not with justice or redemption but with circular farce: Pato remains unrepentant, still lying, still convinced of his misunderstood greatness.

The satire suggests that such figures never change-they persist, swollen like their own hemorrhoids, trapped forever in their delusions.

PATO is a darkly humorous and satirical novella centered on the life of a court bailiff in an imaginary Court, whose defining traits are pathological lying, narcissism, and sexual obsession. The story is not a heroic journey but a grotesque portrait of human folly, exposing how a man's desperate need for recognition turns him into an object of ridicule. The opening chapters establish Pato as an egotistical trickster figure.

He lies compulsively-not for gain but as a reflex. His deceptions are clumsy, transparent, and easily uncovered, yet he repeats them endlessly. This compulsive dishonesty becomes both his weapon and his undoing. Early scandals revolve around his inappropriate behavior toward female colleagues and his laughable attempts at seduction, which reveal his fragile masculinity and inflated self-image. A central motif is Pato's hemorrhoids, described with grotesque detail as if they were divine punishment for his arrogance.

They serve as both a literal ailment and a metaphor for his swollen vanity and chronic irritation with reality. Instead of accepting his condition, Pato dramatizes it, using his pain as yet another excuse to demand sympathy and special treatment. The novella gains psychological depth in his encounters with Abidin Bey, an older colleague who represents wisdom and moral clarity. Their dialogues resemble a philosophical interrogation of Pato's soul, with Abidin asking why he lies, what he hopes to achieve, and whether he understands what it means to live truthfully.

Pato, predictably, dodges these questions with more lies, showing his inability to face himself. The court itself becomes a theater of absurdity. Pato, in his role as bailiff, meddles with secretarial tasks, attempts to impress judges with invented knowledge, and constantly seeks validation. Instead, he earns mockery from colleagues and irritation from superiors. The court-symbol of order and law-is inverted into a stage for petty gossip, disorder, and hypocrisy.

As scandals mount, Pato's collapse accelerates. Therapy sessions and psychological reports are introduced, diagnosing him with narcissism, compulsive lying, and obsessional behaviors. Yet instead of treating these as warnings, Pato embraces them as proof of his uniqueness, convincing himself that ordinary minds cannot comprehend him. His obsessions intensify around two women: Manolya, a lawyer who embodies professional authority, and a young secretary.

His humiliating advances toward Manolya, including a scene where he kneels in her office, cement his reputation as a clown. The secretary becomes a symbol of unattainable innocence, another projection of his fantasies. In both cases, rejection only strengthens his delusions. The private chapters of the novella explore his unhappy home life. A neglected childhood and an indifferent mother left him craving validation.

His wife mocks him openly, stripping away any illusions of domestic authority. Public bravado becomes his way of compensating for private humiliation. By the final chapters, Pato has also sunk into gambling and reckless debt. In a grotesque twist, he even pursues the wife of a married debtor, blending lust, power, and financial desperation into one absurd scheme. The novella ends not with justice or redemption but with circular farce: Pato remains unrepentant, still lying, still convinced of his misunderstood greatness.

The satire suggests that such figures never change-they persist, swollen like their own hemorrhoids, trapped forever in their delusions.

, qui est-ce ?

, qui est-ce ?